Whisper it wistfully, but we’re getting the feeling that – in this age of AI and galloping digitalism – there’s something of a folk/handicraft revival brewing up.

We were thrilled to catch a few songs by Liz Overs (formerly Liz Pearson of Chalk Horse Music) during a cultural soiree at Emma Mason’s gallery in Eastbourne in the autumn, and delighted when – as she’d promised – her latest album Nightjar arrived in the office after the turn of the year.

Her reflective, pensive, melodic voice is accompanied in these largely self-penned folksy pop songs (mixed in with a handful of traditional numbers, for good measure) by accomplished musicians such as Ben Nicholls and Neill MacColl (son of Ewan and Peggy). She sings of love, loss, the changing of the seasons, and local legend.

The Binnie sisters appear as spoken voices on Snow Moon; the cover artwork, titled Winter Solstice, is a print by Jennifer Binnie of a deer-headed neo-naturist figure in a leafless wood. Naturally, the single A Prayer to the Year, which opens the album, was released on December 21. You can stream on YouTube a video of this song, filmed in Friston Forest, made by Dylan Howitt, director of cult cinema hit The Nettle Dress.

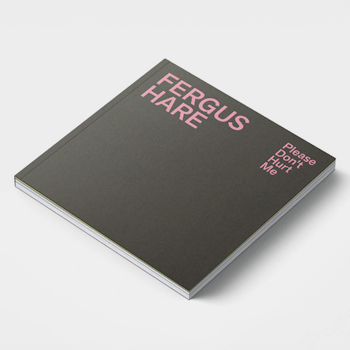

Talking of covers, it’s interesting that the designers of Please Don’t Hurt Me, a signed limited-edition catalogue of 38 paintings by Fergus Hare, have chosen not to use one of his works on the front cover, decorating it with only his name and the title, in pink foil, on a plain slate-grey ground.

Long-term ROSA readers may remember that we used Fergus’ Rose – featuring a woman in a yellow swimsuit lying on the beach – on the front cover of our inaugural issue, including an in-depth interview with the artist inside.

The book opens with a long Q&A with the artist conducted by writer Lynn Ramsson, in which Hare reveals that its title – replicating the title of one of the paintings within – is autobiographical. The interviewer lays bare Hare’s insecurities as an artist, as he explains how he hates to be categorised, and why, when using acrylic, he leaves sections of the canvas unpainted.

Perhaps this explains the designers’ unconventional choice of a cover: sometimes less is more. Whatever the case, it’s well worth delving inside for a selection of Hare’s thoughtful, poignant, beguilingly timeless slices of life.

Between the Broken Glass the People Play is a memoir of (Rottingdean-based) journalist Christine Day’s life in London during the Swinging Sixties. Day worked for teen magazines Boyfriend and Fabulous, interviewing and hanging out with pop musicians and actors on their ascent to superstardom: Mick Jagger, Marianne Faithful, Michael Caine, Bob Dylan, Twiggy, Jimi Hendrix. Throughout this effervescent period she was involved in a passionate and abusive relationship with a beguiling, mentally ill actor. The chapters are billed as ‘fragments’, interspersed with photographs of shattered glass, as she tries to negotiate her way through her increasingly outlandish and difficult lifestyle with the aid of psychotherapy, marijuana and astrology. Day writes in short sentences, each paragraph a self-contained unit. The madcap decade unravels as you turn the pages.

On pages 47 to 54, we look at the sketchbooks of Tadek Beutlich. If you visit the current retrospective of his work at Ditchling Museum of Arts + Crafts, try not to resist the temptation to buy the beautifully illustrated book, republished to accompany the show, Tadek Beutlich, Innovations in Textile and Print, edited by Emma Mason, who holds Beutlich’s archive.

This square-format publication, readable in one sitting, comprises four essays on different aspects of the Polish- born artist’s life and career. There’s a biography by Magdelena Wichtowska, an appraisal of the importance of the 14 years he spent living and working in Ditchling by Stephanie Fuller, an overview of his printmaking practice by Emma Mason, and a dissection of his ‘free-warp’ (loomless) techniques by textile artist Tim Johnson, who’s been much influenced by Beutlich’s multi-faceted work.

A picture gradually emerges of an introverted genius torn by the contradictory factors that shaped his early life. Born in Poland to a German father and a Polish mother, he was reluctantly conscripted into the Nazi army in 1942, captured by the Allies, then volunteered to fight against the Germans in the latter part of the war. He henceforth never settled for long in one place, each move influencing a shift in his working practice.

The book ends with a quote ‘I dislike any complicated involvement in mechanical means’: Beutlich was very much an organic artist, inspired by Polish folklore and the natural world around him, which explains the current resurgence in popularity of the artist in these over-digitised times.

Words by Dexter Lee