Marcus Rees Roberts at Julian Page Projects, in Chichester.

‘How did you come to this dark shore?’

So asked Odysseus, on meeting a long-dead friend, having made the treacherous journey across the River Styx into the Underworld.

The artist Marcus Rees Roberts refers to this spectral reunion in the title of his excellent solo show at Julian Page’s new gallery in Chichester, This Dark Shore, which largely explores, in paintings, prints and artist’s books, the existential crisis of human migration.

For the Styx, read the English Channel. “The vision of those poor souls crossing the Channel and trying to make a better life for themselves has haunted me for years,” he tells me, sat in the gallery a few hours before the exhibition’s private view, amid his dark, almost entirely monochrome works. “And all that time I’ve been trying, in various ways, to depict the sadness and anxiety that is connected with being a refugee.”

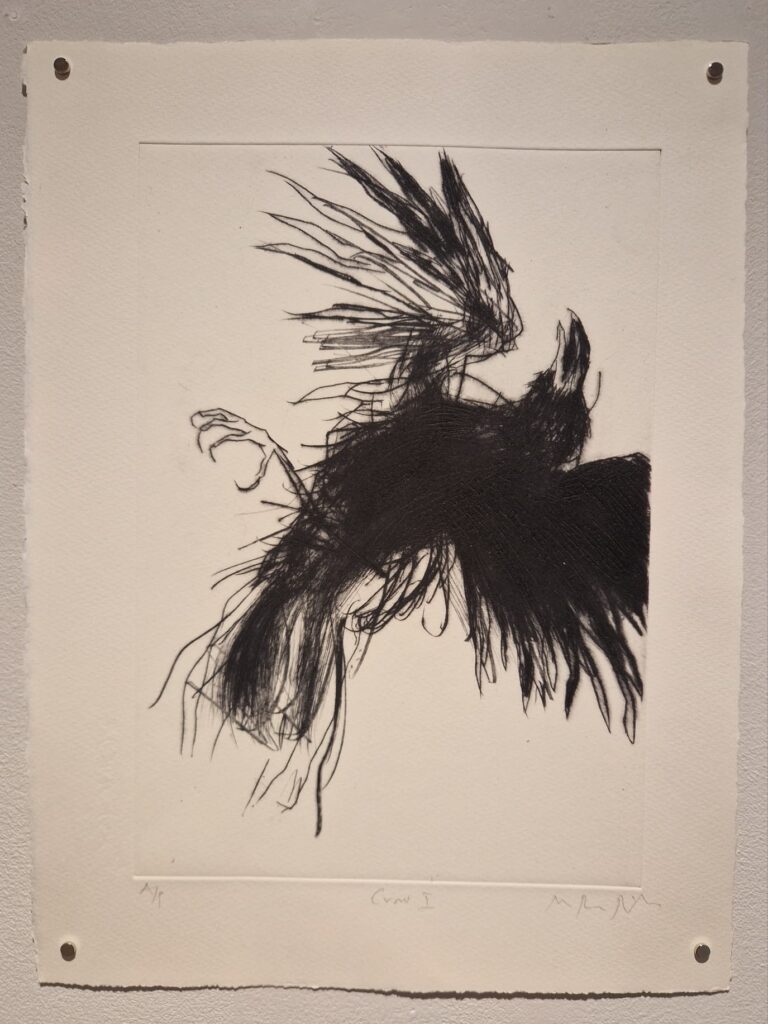

Rees Roberts’ landscapes are rarely scenic, and there are no images of men crowded into boats. He deals in metaphor, creating dry-point prints of birds in distress, indistinct torsos floating in inky blackness, winter trees rising from murky pools, hands reaching vainly into nothingness. The works are oblique, haunted, and formally rigorous, designed to evoke rather than explain. In this series, there is no colour. “This comes from my earliest days of etching,” he says. “Ultimately, colour doesn’t add anything. It’s just a distraction.”

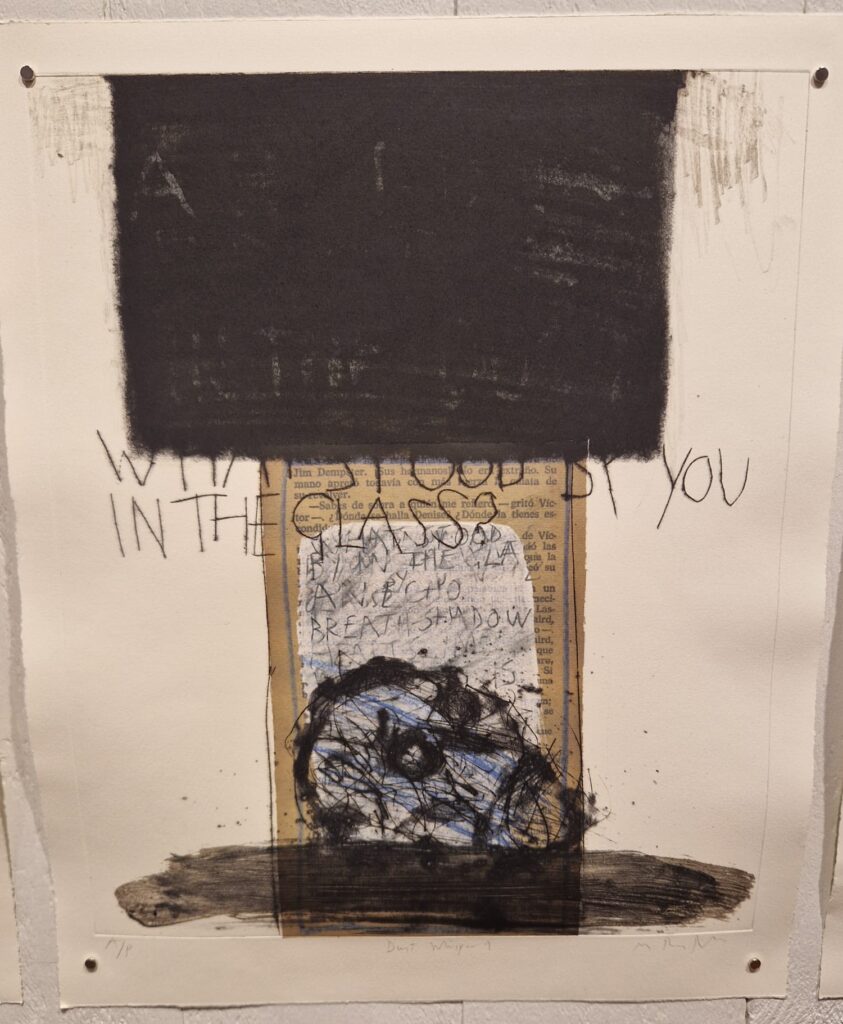

In many works, Rees Roberts incorporates fragments of text, either in scrawled handwriting or underlaid papier-collé documents: official lists of dead refugees, half-erased names, biblical lamentations, the lettering often obscured, or half-obscured by the images. These are not captions but “a sort of insistent whisper behind the image,” suggesting the ethical burden of witnessing. This technique provides a material and ethical rupture, reminding the viewer that the image is constructed, mediated, and haunted by real-world documents and histories.

Rees Roberts admires Albrecht Dürer for his skill as a master engraver, though he eschews the German Renaissance artist’s ‘illusionist’ methodology, which “made the act of making the print invisible, because he wanted to encourage the eye to pass straight through the picture surface into the depicted scene.” He feels much more akin to Francisco Goya, who subverted artistic norms by creating a duality by which “the eye is held at the surface but simultaneously drawn through into the represented space.” A similarly subversive influence on the artist’s development was the German Expressionist filmmaker Robert Wiene, who, in his 1920 work The Cabinet of Dr Caligari, “dismantled all those carefully constructed conventions of filmic realism” with his jagged sets, distorted perspectives, and psychological intensity.

Another inspiration, perhaps surprisingly, is Pablo Picasso’s final etching series, particularly Suite 347 and Suite 156, created in the last years of his life. “There’s this sad awareness of his age, of his impotence, of death. And still, there are these beautiful women he’s gazing at wistfully and hopelessly. I think they’re incredibly beautiful, moving images.” He has less time for William Blake, another printer who juxtaposed lettering and figuration: “there isn’t a dynamic, tense relationship between the text and the image: it’s just simply an inert relationship… besides, he just doesn’t cut it as a visual artist.”

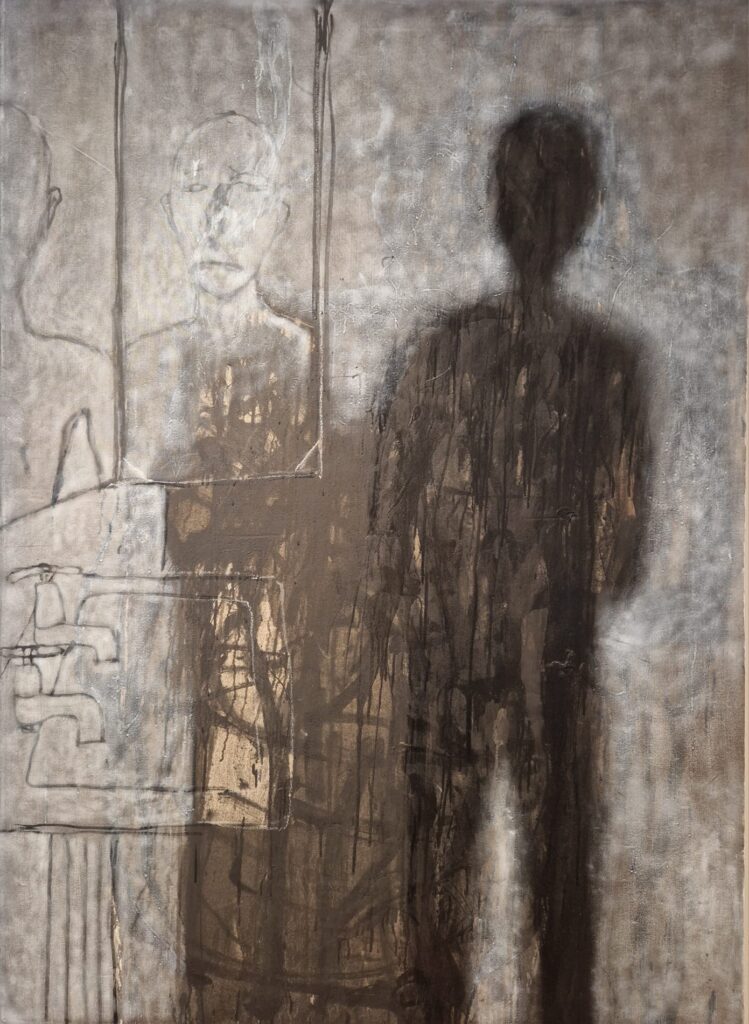

The largest works in the exhibition are a series of paintings which share a common concern with displacement, historical trauma, and the ethics of representation. These works, like Rees Roberts’ later prints, adopt a visual idiom of fragmentation and metaphor, exploring the soul-scorching last night of German-Jewish philosopher Walter Benjamin, on the run from the Nazis in 1940. Benjamin, whose work redefined how we think about history, memory, and the role of culture in shaping consciousness, killed himself in the French border town of Portbou, on learning that he would not be able, as planned, to continue his journey into Spain the next day. Rees Roberts’ palette is subdued – greys, blacks, and muted ochres dominate, with limited but highly effective smears of red – evoking the “dusty and grey” atmosphere he associates with a town he has passed through many times. The compositions are rendered in a psychic blur, as if the viewer is seeing through memory, or melancholic mist.

Rees Roberts is a self-proclaimed atheist, stating: “I love everything about the church, but I just have no faith whatsoever. I cannot believe in God. So as far as I’m concerned, this life is the end of it.” Nonetheless, like Benjamin before him, he understands the spiritual power of the Old Testament doctrine, turning to the Bible in his series of dry-point prints reflecting on the war in Ukraine. Found images from mass media sources, and reworked in dry point, are annotated with quotes from the Book of Jeremiah, thus comparing the conflict with the destruction of Jersusalem, combining the rawness of current events with the solemn cadence of scripture. Rees Roberts has donated prints from the Ukraine series to raise funds for humanitarian aid, and is also donating proceeds from two haunting dry-point prints in this exhibition to aid children affected by the conflict in Gaza.

Rees Roberts’ refusal to aestheticise suffering is not a rejection of beauty, but a redefinition of it. “People have said to me, how can you make something beautiful about an ugly thing?” he reflects. “And I think that’s a mistake. You’re confusing aesthetic judgment with moral judgment. They shouldn’t be conflated in that way.” His works are not consolations, then, they are insistences. Each print, each painting, each whispered fragment of text demands that we look, not away, but deeper.

In This Dark Shore, Rees Roberts does not offer resolution. There are no answers, no redemptive arcs. Instead, he gives us a visual language of mourning and metaphor: a way to hold the unbearable without simplifying it. The exhibition offers a kind of ethical architecture, built from fragments, shadows, and the residue of history. It asks what it means to witness, to remember, and to make art in the aftermath of loss and war. And yet, there is great beauty shining through the horror. “I wouldn’t let it pass if I didn’t think it had something beautiful in it,” he says, as a parting shot. “I’d keep working at it until I thought it was right.”

Alex Leith

This Dark Shore runs at Julian Page Projects until November 1. Please note: the gallery will be closed from 23–27 September due to participation in the British Art Fair.