Jane Bown, ‘the British Cartier-Bresson’

All images © Jane Bown Estate

“Other people take photographs. I try to find photographs.”

So said Jane Bown, the Observer newspaper’s go-to portrait photographer for some six decades, and a talented photojournalist to boot, whose reputation soared towards the end of her career, and just keeps on soaring after her death, aged 89, in 2014. A retrospective of her work, the latest in a succession of solo exhibitions, curated by Dr Loucia Manopoulou, is forthcoming at Newlands House Gallery this autumn. She referred to herself as a ‘hack’, but Bown’s lifelong career as a jobbing newspaper photographer belied her innate talent. She is, posthumously, becoming seen as an artist: Lord Snowden and Germaine Greer both referred to her as ‘the British Cartier-Bresson’, and it’s easy to see why.

As a child she was passed round “like a game of pass the parcel”, she revealed in the poignant documentary Looking for Light, released just before she died. She never met her father, and it wasn’t until she reached the age of 12 that she realised one of the two ‘aunts’ who was currently looking after her was, in fact, her mother, who she never forgave.

Having worked during WW2 as a chart corrector for the WRNS (she helped plot the D-Day landings) Bown was at a loose end after the war, and, though she had little experience of taking photographs, she managed to wangle her way onto the only full-time photography course in the country, at Guildford School of Art. She was a ‘terrible student’ until she bought herself a Rolleiflex camera, and a close-up shot of a horse’s eye caught the attention of the Observer’s picture editor. Her first commission for the paper, in 1949, was a portrait of the philosopher Bertrand Russell, having breakfast in a London hotel with his new wife. “I was terrified,” she later remembered, “and I had little idea who he was. But the light was good.” The striking profile of Russell perfectly captured his stern-yet sympathetic personality. And so began her lifelong career at the newspaper, and a lifelong search for the perfect light.

In the 60 years she worked for the Observer, eventually swapping her Rolleiflex for an Olympus OM-1, she took portraits of thousands of celebrities, usually working with what very little time was available after her journalist companion had finished their interview. It’s pointless to try and name names: she photographed Beatles and Rolling Stones, PMs and Poet Laureates, Hollywood royalty and real royalty. She photographed every Prime Minister from Harold Macmillan to Gordon Brown, and was commissioned to photograph Queen Elizabeth on the monarch’s 80th birthday, having just passed that landmark herself.

No great follower of the high life, she had little truck for celebrity (once asking ‘who is Mr Jarvis Cocker?’) and her unassuming manner – she was short, and quiet, and rather dowdily dressed, pulling her camera out of a wicker shopping basket – went some way to putting her subjects at ease. As did the lack of paraphernalia she incorporated into the shoot: she never used flash, only available light, used the back of her hand as a light meter, and very rarely used more than one roll of film. Her journalist colleagues describe her circling her subjects, until she intuited the right angle; she uttered an involuntary catch phrase when she’d ‘found’ her subject: ‘ah yes, there you are.’ Sometimes she found them straight away, other times she had to wait. “The best shot,” Bown often said, “was usually the first or the last.”

On one occasion in 1976, she was granted just three frames by Samuel Beckett, who was trying to escape an organised photo shoot at the Royal Court Theatre, and who she had cornered down a dingy alleyway by the stage door. She took five. One of them has become the defining portrait of the Irish playwright, capturing a kindly tragedy behind eyes that shine out from that wrinkle-riven face. “There was no question of me not getting the shot,” she later remembered. “I just couldn’t have gone back empty handed.”

She also accompanied print journalists on news stories, working with the likes of Johnny Gayle, Polly Toynbee and Andrew Billen, photographing hop pickers and dock workers, peace demonstrators at Greenham Common and factory workers in Rochdale, as well as revellers at iconic events such as Glastonbury and Glyndebourne. In these shoots, often photographing people from behind or above, she demonstrated a talent for creating beautifully balanced compositions, marrying the shapes of bodies to the landscapes surrounding them, always telling a story within the story. One of the pictures we’ve used to illustrate this piece, of a couple at Glyndebourne, the man carefully carrying the picnic goodies, the woman waving her lace shawl like a matador’s cape, is a good case in point.

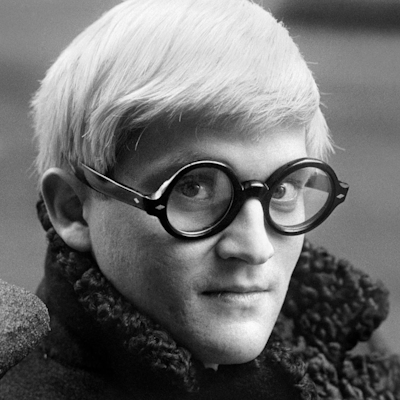

The image above captures Duncan Grant, splendid in a straw sombrero, at Charleston in 1978, shortly before his death. The use of natural light and quiet framing capture the artist’s powerful frailty with characteristic subtlety. And those piercing eyes! With Jane Bown, it was always about the eyes. And more: it was always about what was behind the eyes.

Jane Bown shot in colour for three years in the 60s, after the Observer brought out its colour supplement, and she hated it. “Colour is too noisy,” she once said, “the eyes don’t know where to rest.” Monochrome was her milieu: black and white and a thousand shades of grey, painted by what light the setting afforded (though in the winter months she brought an Anglepoise lamp in her basket, to help out). She never took to digital photography, hating the very idea of it: “when digital photography came in, that’s when I went out,” she said, in the Looking for Light documentary.

She took her last photograph for the Observer in 2009, aged 84, of the Mancunian pop-poet John Cooper Clarke. After her retirement she would travel up to the newspaper’s offices every week, and sit in the foyer in her wheelchair, catching up with former colleagues. Has any other journalist shown such loyalty to one newspaper? Bown was married, and had three kids, but at her wedding she was given away by Observer editor David Astor, and in a sense she was also married to Britain’s oldest Sunday newspaper. In Looking for Light she is asked by filmmaker Luke Dodd why she never left the Observer: surely she could have got better paid by a different paper? I could never leave the Observer,” she replied. “The Observer was home.”

Words by Antonia Gabbassi

Jane Bown: Play Shadow is on at Newlands House Gallery from November 1 to February 15. The exhibition is curated by Dr. Loucia Manopoulou.