Hugh Philpott enjoys an orchestral bus-and-hike trip in the West Sussex downlands.

Today I am on a quest to discover ‘England’s green and pleasant land’. My feet will be walking, perhaps not on a ‘mountain green’, but certainly up a steep hill or two. The forecast is fair, so happily, the mills won’t appear too satanic, the hills not too clouded and the pastures pleasant.

I need to fess up. I have not included Jerusalem in the classical playlist I have created to accompany me on my trip. This short but-huge choral work, with words by William Blake (Felpham), and music by Hubert Parry (Rustington), does indeed sum up Englishness and strongly evoke the Sussex landscape, but it is not today’s ‘vibe’.

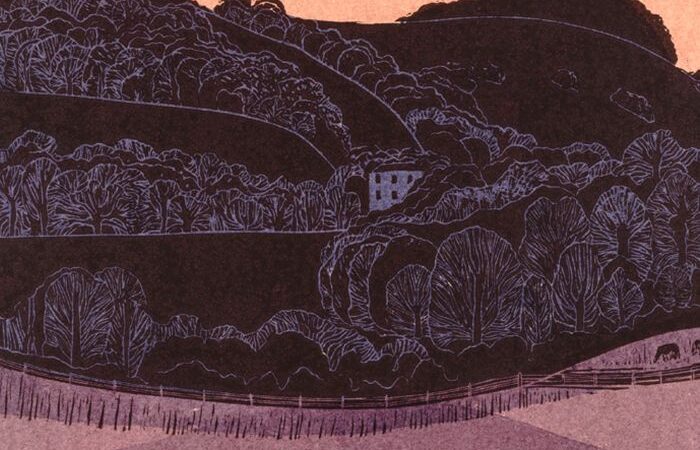

In the Spring issue I explored works of 20th-century classical music inspired by towering cliffs, rolling hills and roiling waves of the East Sussex coast. I found a lush and multi-layered soundscape interpreted through expansive orchestral writing. This time I am exploring the music which tells the story of the Sussex countryside. I am searching for a more introspective and contemplative experience focusing on quiet spaces, micro landscapes and detail.

Notwithstanding his surname, John Ireland was very much an Englishman, and one steeped in the lore and nature of Sussex, to where he eventually retired. He took over a converted mill in the hamlet of Rock, near Washington, which was his home until he died. Ireland’s A Downland Suite was originally composed for brass ensemble to play in a competition. The band didn’t win, but we still have the suite. It was soon also arranged for strings, which creates a completely different mood. I have never been able to decide which I prefer and so include both. The brass version is robust enough for the rail part of my journey taking me to Burgess Hill. But now, on the number 100 bus bound for the Green Park Farm stop, just before Pulborough, I 66 decide to listen to the strings. In both versions it is simple and direct music which speaks of ancient places hidden in plain sight and steeped with pagan lore. It conjures a brightly bucolic procession of images telling a story of gently rolling chalk hills, grasslands and woods. Put simply, it’s nice music and does exactly what I need it to do, as I stare out of the window.

The suite was in part inspired by Ireland’s walking in places like Chanctonbury Ring and the surrounding grasslands and sparse woods. Seeking to adhere to the method-acting form of writing, I make this my first destination and the one which will demand a serious walk. The Green Park Farm stop is the closest on public transport to Chanctonbury Ring. I get out there and start my hike.

I have pre-downloaded my chosen tracks to guard against mobile coverage black-spots. There is nothing worse than breaking up in the middle of the andante cantabile section of a finely executed piano cadenza as you beat back the brambles with your newly acquired stick. I walk with ease along the dappled lanes which lead away from the main road towards the Ring. Soon the lane gives way to dusty chalk and flint paths. I choose the shorter path up, but it transpires this is also the steeper route and so time-saved is probably also time-spent because the walking is tougher. It matters not. I keep telling myself the step-counting app on my phone will be very happy. Or will it? Does the lack of signal mean it won’t record my efforts? I mull this for a moment as the mood of my playlist changes. Next up is Legend, also by Ireland.

As I reach the beech copse at the top, it dawns on me I have been here before. The trees were originally planted by Charles Goring in 1760, whose family still own Wilton Park and Wiston House, but lease it to the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. It’s funny how worlds collide. These days there are fewer mature trees than I remember from that first visit over 40 years ago, while working on government business, but then that was before the great storm of ’87, which prematurely felled so many of our ancient woodlands.

From up here the views are indeed far-reaching. Tennyson, another Sussex resident, says it so simply: ‘Green Sussex fading into blue/ With one grey glimpse of sea’.

Tucking into my packed lunch, I think again about John Ireland. He would often pack some sandwiches and a flask and go out hiking on the Downs. I imagine him up here with his notebook. It is such a gin-clear day that I am sure that, if I knew what I was looking for, I could see Harrow Hill, which he would visit, and which inspired Legend. It’s a haunting ethereal piece, which Ireland composed in 1933. Perhaps one of his most mysterious and psychologically charged compositions, it is in stark contrast to much of his other work, imbued with a pastoral or romantic sensibility. Ireland reported to a contact, who shared his interest in the occult, how he had witnessed children dancing on Harrow Hill in old-fashioned clothes. He believed he had seen the ghosts of children from a medieval leper colony which had once occupied that part of Sussex. The thought makes me shudder. I need to move on.

I want to find the village of Washington. It’s there I can catch the Compass 100 again and make my way to Storrington. At one point on the way down, as I survey Worthing in the distance and the sea beyond, I am forced to leap for safety to the side of the chalky path. My earbuds are too effective to have offered sufficient warning: a dusty cloud masks three cyclists. Any sense of spiritualism or dancing medieval waifs evaporates. It’s a shame, but I am soon making easier progress on the descent and then on the level once again walking along the leafy lane, passing a small car park and on the way to the village, where I rejoin the 100 bus route. As I wait, I listen to the next track on my playlist.

Arnold Bax isn’t usually regarded as part of the English Pastoral School. He is mostly remembered as one of the greatest British symphonists, and for his incidental music for stage and cinema. One weekend in 1940, escaping a war-torn London, he decided to spend a weekend at the White Horse Inn in Storrington. He liked the place so much that he stayed for the rest of his life. That period also saw some music, that I would certainly describe as English Pastoral, so for my next track I have chosen Maytime in Sussex (popularly known as Morning Song). Bax wrote this when he was Master of the King’s Music, to honour the coming of age of a young Princess Elizabeth. Although it features a full orchestral setting, it is the piano, as soloist, which speaks gently as the main voice. It’s a sparklingly elegant piece with a delightful hop and skip in its theme. That theme repeats and varies itself as it bounces around from the piano to the other instruments with a fairy-like diaphanous quality. It is pure joy.

While in this area I want to mention Edward Elgar’s Sussex retreat, Brinkwells, just north of Fittleworth, alas too far for me today. However, I want to include Elgar so that I can add his beautiful cello concerto. This didn’t really become popular until the 1960s when Jacqueline du Pré and her then husband, Daniel Barenboim, one of classical music’s golden couples, immortalised it. The concerto is more elegiac and contemplative than Elgar’s earlier output and, as one American critic once said, its playing requires ‘a reserved dignity that is peculiarly English’. It was never truly popular in Elgar’s day but is now a staple of the repertoire.

I don’t have to wait long for the Compass 100 heading back towards Burgess Hill. The last leg is just a few stops, but there is time enough to make a quick return to John Ireland. Just south of here you will discover the River Arun wetlands, where Ireland liked to spend time. The area, rich with wildlife, inspired him to write Amberley Wild Brooks, a little gem for piano. This impressionistic music speaks of a secret, wild and free place. Nowadays there’s an RSPB reserve nearby, but in Ireland’s day it was rarely visited.

I get off at Pulborough station, which is the end of my journey. My feet have started to complain about the hard and dry chalk paths of my Chanctonbury Ring detour, but this does not detract from the joy of my walk ‘on England’s pleasant pastures’. Remember where I started today with Hubert Parry, of ‘Last Night of the Proms’ fame? Well, I doubt Parry ever strayed up onto the Downlands in the way John Ireland did, nor live above a village pub like Arnold Bax, but he was a sympathetic and sensitive composer who understood the meaning of place, particularly in Sussex. Parry was living in Rustington when he composed Jerusalem. There’s a blue plaque outside his old house on Sea Lane. But great though that work is, there is a lot more to him than huge anthemic choral pieces marking state and national occasions.

I want to finish with something simpler, and so choose Parry’s set of ‘Shulbrede Tunes’. Here he allows himself to reveal a more domestic and intimate side. This lovely set of miniatures, arranged as a suite for piano, speak of hidden Sussex, and family. He composed the set for his daughter Dolly, who lived at Shulbrede Priory, a former medieval monastic house in West Sussex, up where it meets Surrey and Hampshire. There is plenty here to enjoy, and it is certainly a green and pleasant way to conclude my journey.

Listen to the ROSA Magazine ‘West Sussex Landscape’ playlist on Spotify.

- A Downland Suite, John Ireland, conducted by James Stobart, London Collegiate Brass

- John Ireland arr. Composer/G. Bush: A Downland Suite for string orchestra (1932 arr. 1941/1978)

- Legend, John Ireland, John Lenehan on piano, conducted by John Wilson, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra

- Maytime in Sussex, Arnold Bax, Ashley Wass on piano, Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra

- Cello Concerto, Elgar, Jacqueline du Pré, conducted by Sir John Barbirolli, Warner Classics

- Amberley Wild Brooks, John Ireland, Mark Bebbington on piano

- Shulbrede Tunes, Sir Hubert Parry, Peter Jacobs on piano